Lessons in Humanity from Mumbai’s Third-gender Hijras. Post-Magic: The Female Naxalite at 50 in Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness and Neel Mukherjee’s A State of Freedom. The (In)Significance of Small Things: Data, Identity, and the Dilemma of Recovery in Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Transgender Studies Quarterly 1 (3): 320–337.Įdelman, Lee. Decolonizing Transgender in India: Some Reflections. Current Biology 23: 298–300.ĭutta, Anuridha, and Raina Roy. Dung Beetles Use the Milky Way for Orientation.

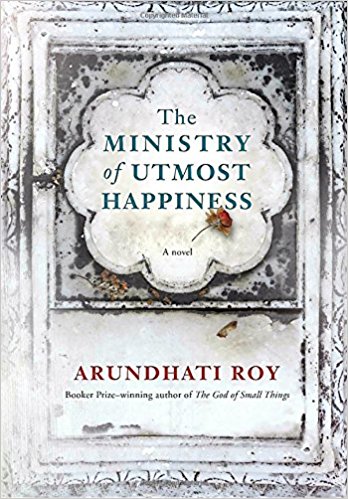

Social Text 61: 141–166.ĭacke, Marie, Emily Baird, Marcus Byrne, Clarke H. When the (Hindu) Nation Exiles Its Queers. Durham: Duke University Press.īacchetta, Paola. At the same time, I argue that The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, which expressly refuses many of the terms of contemporary queer discourse in the West, also highlights the limitations of that body of theory-whose utopian ideals often exclude Indian lifeways and kinship structures-for South Asian literary studies. Building on both Sara Ahmed’s The Pursuit of Happiness (2010) and Angela Jones’s claim that “queer futurity is not just about crafting prescriptions for a utopian society… but making life more bearable in the present, because in doing so we create the potential for a better future” (2013, 2), this chapter uses queer theory to illuminate representations of a resistant present and the potential for a radical future in Roy’s most recent novel. Moving Worlds: A Journal of Transcultural Studies 18 (1): 100–112, 2018), and offered no extended engagement with queer theory. Writing in the Necropolis: Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Romancing the Other: Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. Despite being one of India’s most prominent literary works to center a hijra character, scholarship on the novel to date has primarily focused on issues of class (Lau and Mendes. While Filippo Menozzi reads this rejection of the narrative of linear progress, as indicative of Roy’s complex relationship with realism (2018, 28), I argue that Anjum’s insistence on an alternative present can best be understood as an articulation of queer futurity, whose moment of titular happiness is expressly tied to various forms of queer kinship, expressed not as an ultimate goal but in the novel’s, and our, present. In a moment of mistranslation and cultural misunderstanding, however, Anjum instead states: “e’ve come from there…from the other world” (113–114).

When Anjum, the hijra main character of Arundhati Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness (2017) attends an anti-corruption protest in New Delhi, she encounters a set of activist filmmakers asking attendees to create a message of optimism by stating “another world is possible” on camera.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)